-

Tips for becoming a good boxer - November 6, 2020

-

7 expert tips for making your hens night a memorable one - November 6, 2020

-

5 reasons to host your Christmas party on a cruise boat - November 6, 2020

-

What to do when you’re charged with a crime - November 6, 2020

-

Should you get one or multiple dogs? Here’s all you need to know - November 3, 2020

-

A Guide: How to Build Your Very Own Magic Mirror - February 14, 2019

-

Our Top Inspirational Baseball Stars - November 24, 2018

-

Five Tech Tools That Will Help You Turn Your Blog into a Business - November 24, 2018

-

How to Indulge on Vacation without Expanding Your Waist - November 9, 2018

-

5 Strategies for Businesses to Appeal to Today’s Increasingly Mobile-Crazed Customers - November 9, 2018

Luke Batty inquest: Perpetrators of family violence must be made accountable

Judge Ian Gray on Monday found Luke’s death was not forseeable, and that no individual person or agency should be held responsible, other than the 11-year-old’s father, Greg Anderson, who attacked and killed his son at cricket practice in Tyabb on February 12 a year ago.

Advertisement

The Victorian coroner Ian Gray says Luke Batty’s murder was a “tragic death of a young life full of promise”.

‘Luke’s findings helped me realise, and through the journey before the inquest, Greg (Luke’s father) was never made accountable, not once’.

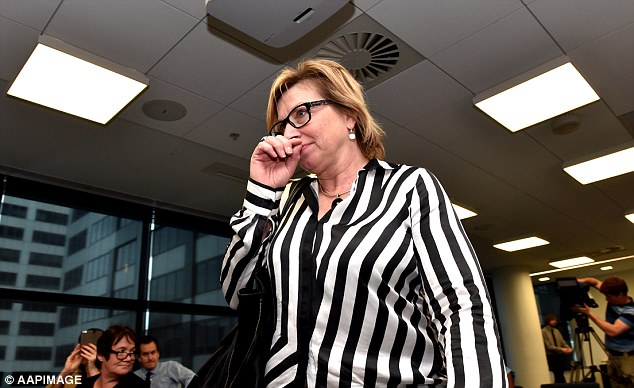

Ms Batty was in court as Judge Gray handed down his findings, seated close to a framed photograph of herself and her son.

‘People do the best they can with their training, with the information they have available, with the resources they have, ‘ she said. He also called for reviews of the bail and family law acts.

“This is the first time in Australia that family violence has been given such a central focus within any police force”.

Judge Gray said a proposal to develop a central agency in family-violence cases was a worthy one, although resourcing was a potential concern.

Ms Batty was praised as a loving and thoughtful mother who was “completely motivated by her deep love for her son”.

“And if I look back over the year since Luke’s (death), at the inquest, in that building, there are some awesome things that have happened”. “We have to look at the issues around privacy, we have to look at a more integrated collaborative manner, we have to look at the safety of women and children and not place the responsibility on their shoulders”.

The inquest was told that about 15 months before the murder Anderson produced a knife while in the auto with his son and said: “This could be the one to end it all”.

An Australian coroner has said the killing of Luke Batty in February 2014 could not have been foreseen.

‘It’s a monumental day, ‘ Ms Batty told reporters in Melbourne. Gray said Victoria police should integrate into their database a way of signalling that there are concerns about the mental health of a perpetrator.

Anderson’s history included an assault on Ms Batty in 2012, for which he was not formally charged until early 2013.

Police prosecutors told the inquest of a lack of compelling reasons why Anderson would be denied bail in each case. At the time, there were four warrants out for Anderson’s arrest, two intervention orders out against him and he was facing charges related to viewing child abuse material. Those problems have since been fixed. Questions as to whether Anderson was in fact mentally ill were often raised by police and Rosie Batty during the 13 days of inquest evidence previous year, with one police officer insisting he was “bad, not mad”.

Advertisement

He also found there had been delays in the justice system and neither police or the Department of Human Services had investigated a knife threat made by Anderson. But she decided against doing so because she did not want to embarrass her son, and she had been traumatised by previous attempts to have police arrest Anderson at the oval.