-

Tips for becoming a good boxer - November 6, 2020

-

7 expert tips for making your hens night a memorable one - November 6, 2020

-

5 reasons to host your Christmas party on a cruise boat - November 6, 2020

-

What to do when you’re charged with a crime - November 6, 2020

-

Should you get one or multiple dogs? Here’s all you need to know - November 3, 2020

-

A Guide: How to Build Your Very Own Magic Mirror - February 14, 2019

-

Our Top Inspirational Baseball Stars - November 24, 2018

-

Five Tech Tools That Will Help You Turn Your Blog into a Business - November 24, 2018

-

How to Indulge on Vacation without Expanding Your Waist - November 9, 2018

-

5 Strategies for Businesses to Appeal to Today’s Increasingly Mobile-Crazed Customers - November 9, 2018

Gene therapy shows hope for the deaf to hear again | Zee News

Research revealed today shows the revolutionary technique is capable of fixing faulty DNA to let genetic deaf mice hear again.

Advertisement

Scientists at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School have restored hearing in deaf mice by replacing a mutated gene with a healthy version by injecting it into their ears.

There are more than 70 different genes that are known to cause deafness when mutated.

Holt and lead author Charles Askew, a Harvard grad student, are optimistic about the possibilities for reversing inherited deafness.

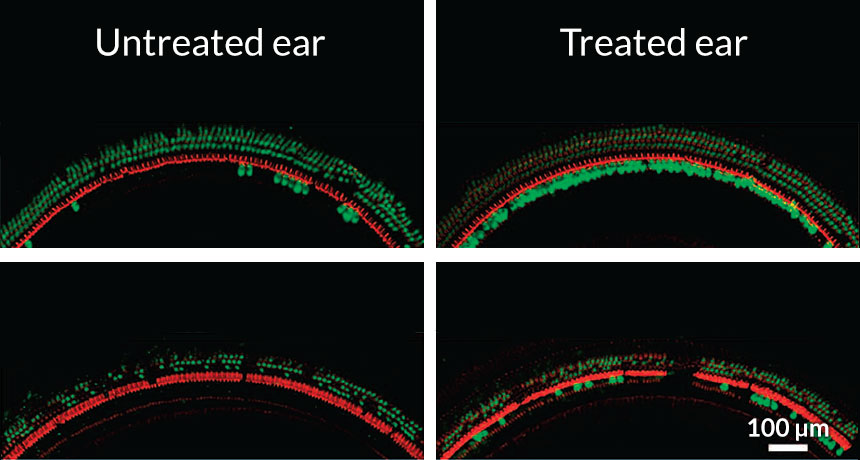

A mutation causes sound-sensing cells (green) to die off quickly in deaf mice, but gene therapy can save these cells (right) in mice given a virus that delivers a working gene.

Researchers in the U.S. have successfully corrected inherited deafness in a strain laboratory mice that is a realistic animal model of the mutations that causes congenital deafness in between 4 and 8 per cent of deaf children. In this form, less common than the recessive form, a single copy of the mutation causes children to gradually go deaf beginning around the age of 10 to 15 years.

In the mice missing the gene, the working genes restored the ability of sensory hair cells in the ear to respond to sound by producing measurable electrical currents, and they also restored activity in the portion of the brainstem involved in hearing.

The mice that recovered hearing received a partial fix.

Scientists from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne and the Boston Children’s Hospital, tested hearing in newborn mutant mice by seeing how high they jumped when startled by a noise.

In the mice with the mutated TMC1 gene, the working genes were effective at the same cellular and brain level, but in addition, were partially successful in restoring a level of actual hearing, the researchers reported in the journal Science Translations Medicine. Cell bodies are below the bundles.

The viruses used to deliver the genes are safe and are already in use in other human gene therapies for blindness, heart disease, muscular dystrophy and other conditions, Holt noted. The researchers screened various types of AAV and various types of promoters to choose the best-performing combination.

“If you think how much it will cost to really go through all the clinical trials until you actually have approval, this will I fear really limit the chances to put this into practice”, he said. “Cochlear implants are great, but your own hearing is better in terms of range of frequencies, nuance for hearing voices, music and background noise, and figuring out which direction a sound is coming from”.

Holt believes that other forms of genetic deafness may also be amenable to the same gene therapy strategy.

Babies born with severe to profound hearing deficits occur in up to three per 1,000 live births, the statement said.

Holt said that he could envision patients with deafness having their genome sequenced and a tailored, precision medicine treatment injected into their ears to restore hearing.

The ear’s sound-sensing hair cells convert noises into information the brain can process. When sound waves wash over the microvilli, they wiggle and the mechanical stimulation causes the channel to open. But along with evidence from earlier studies, these results show that gene therapy can treat deafness, Lustig says.

The TMC1 gene, along with an associated gene called TMC2, codes for a protein that is made in the tip of the tiny, hair-like projection or “microvilli” of the inner ear. “We know they were maintained in the mice for a few months, but we want it to be retained for a lifetime”, says Holt.

Advertisement

Staecker is one of the scientists conducting the first study attempting to use gene therapy to restore hearing in people.