-

Tips for becoming a good boxer - November 6, 2020

-

7 expert tips for making your hens night a memorable one - November 6, 2020

-

5 reasons to host your Christmas party on a cruise boat - November 6, 2020

-

What to do when you’re charged with a crime - November 6, 2020

-

Should you get one or multiple dogs? Here’s all you need to know - November 3, 2020

-

A Guide: How to Build Your Very Own Magic Mirror - February 14, 2019

-

Our Top Inspirational Baseball Stars - November 24, 2018

-

Five Tech Tools That Will Help You Turn Your Blog into a Business - November 24, 2018

-

How to Indulge on Vacation without Expanding Your Waist - November 9, 2018

-

5 Strategies for Businesses to Appeal to Today’s Increasingly Mobile-Crazed Customers - November 9, 2018

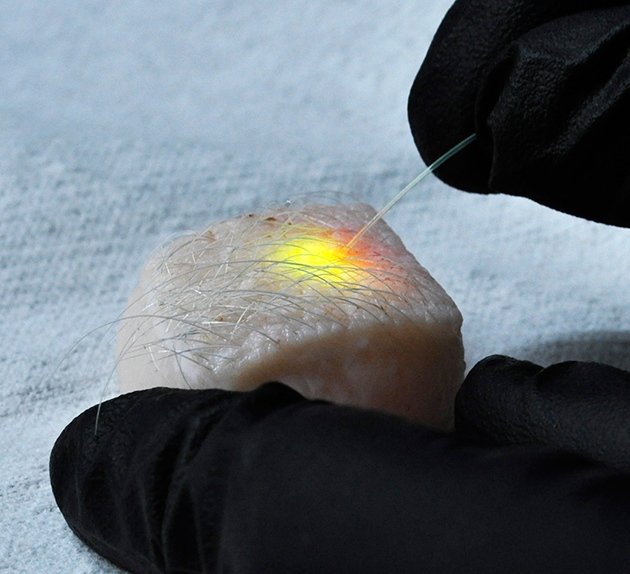

Harvard scientists have turned fat cells into lasers

They may sound like weapons for Ant-Man’s next nemesis, but the microscopic lasers could greatly improve biologists’ ability to track the movement of individual cells.

Advertisement

Yun and Humar used three different methods to create their intracellular “micro-lasers”. The first involved injecting oil droplets that had been embedded with different dyes into the cell.

Scientists have turned individual cells into miniature lasers by injecting them with droplets of oil or fat mixed with a fluorescent dye that can be activated by short pulses of light. In both instances, pumping our bodies by using a heart beat of light provided a residing laser beam, like the light got rubbed on inside and of course the chamber shone.

The everyday kind of laser we’re all familiar with works by bouncing light back and forth between mirrors.

Handily, pig cells contain “nearly perfectly spherical” fat balls, which are conducive to lasing by resonance when supplied with a suitable light source. (Just shining a light on the skin’s surface won’t do it, because the fat cells are underneath.).

It’s already common for researchers to tag cells with dye.

“The fluorescent dyes now used for research and for medical diagnosis are limited because they emit a very broad spectrum of light”, explains Seok Hyun Yun, PhD, of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at MGH, corresponding author of the report.

The new method of turning cells into tiny lasers makes it much easier to distinguish between tagged cells since lasers have a more narrow range of wavelengths. “In principle, it could be possible to individually tag and track every single cell in the human body”, he and Yun wrote in a blog post for Discover. “Imagine rather than a biopsy for a lump that doctors suspect to be cancer, cell lasers helping determine what it’s made of”.

Advertisement

“One immediate application of these intracellular lasers could be basic studies, such as understanding how cells move and respond to external forces”, says Yun, an associate professor of Dermatology at Harvard Medical School. As New Scientist reported, a group at the University of St. Andrews in the UK has also worked with using macrophages to create intracellular lasers.