-

Tips for becoming a good boxer - November 6, 2020

-

7 expert tips for making your hens night a memorable one - November 6, 2020

-

5 reasons to host your Christmas party on a cruise boat - November 6, 2020

-

What to do when you’re charged with a crime - November 6, 2020

-

Should you get one or multiple dogs? Here’s all you need to know - November 3, 2020

-

A Guide: How to Build Your Very Own Magic Mirror - February 14, 2019

-

Our Top Inspirational Baseball Stars - November 24, 2018

-

Five Tech Tools That Will Help You Turn Your Blog into a Business - November 24, 2018

-

How to Indulge on Vacation without Expanding Your Waist - November 9, 2018

-

5 Strategies for Businesses to Appeal to Today’s Increasingly Mobile-Crazed Customers - November 9, 2018

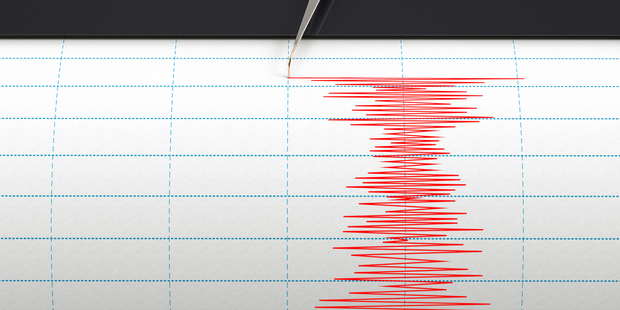

Odds of mega-quake rise at high tide

Ocean water is moved by the combined gravitational pull of the sun, moon and earth, which all line up in a row at high tide.

Advertisement

Ide and colleagues noticed the December 26, 2004 Sumatran quake, most notable for its horrendous, deadly tsunami, occurred near the time of full moon and spring tide. But going back to the 1800s, nobody had demonstrated firm evidence for this.

In a review of the world’s largest temblors, a team of Japanese scientists found that powerful earthquakes tend to occur during periods of strong tides, such as during the full moon and new moon, when the difference between high tide and low tide is greatest.

Their research has been published in the journal, Nature Geoscience.

It was possible that knowledge of large tides in earthquake-prone regions could help in probability analyses.

But one theory holds that they begin as smaller fractures that build up via a cascading process.

Large, deadly earthquakes in Indonesia in 2004, which triggered the Boxing Day tsunami, the magnitude 8.8 quake in Chile in 2010, and the magnitude 9 natural disaster and subsequent 10-metre tsunami in Japan in 2011, were all part of the study, which indicated the frequency of big quakes increased as tides increased in size and movement.

But University of Melbourne Associate Professor Mark Quigley warns it’s a hypothesis and not an absolute finding. These included the 2004 Sumatra quake, the 2010 Chile natural disaster and the 2011 Japan natural disaster.

The level of media interest and coverage at that time to lunar-based predictions of the next “big” quake, led Dr Quigley to ask one of his masters students to research the issue.

Not all large earthquakes are caused by the moon’s movements.

To be sure, many earthquakes will still happen when tidal stress is low, Ide said.

The study’s other authors are Suguru Yabe and Yoshiyuki Tanaka, also of the University of Tokyo.

The idea that tides can affect earthquakes is not new. The nearest new moon was on March 4 and the full moon on March 19.

In other words, during a new moon or full moon, a small increase in tidal stress might be enough to encourage a very small fracture into a major quake.

“It is important to recognise that I am not saying that tidal stresses are unimportant things to consider within the variety of processes that may influence natural disaster behaviour”. Ide and colleagues point out that at least three other quakes in November 2006, January 2007 and September 2007, were not correlated with times of large tidal stress.

Mr Quigley said researchers should be focusing more on minimalising the impact of earthquakes, instead of predicting them.

“The probability of a tiny rock failure expanding to a huge rupture increases with increasing tidal stress levels”, the study said.

“Earthquakes are almost a random process”, he said. He cautions that “even if there is a strong correlation of big earthquakes with full or new moons, the chance any given week of a deadly quake remains miniscule”, making predictions rather unhelpful.

However, Quigley said the tidal stresses before and after the March 2011 Japan quake were higher in the 30 days before and after the quake and there was not a clear link between stress measurements and the timing of the quake. This certainly would not have helped in the Tohoku example.

Advertisement

The scientists, from the University of Tokyo, looked at data about tidal stress history from global, Japanese and Californian quake catalogues.