-

Tips for becoming a good boxer - November 6, 2020

-

7 expert tips for making your hens night a memorable one - November 6, 2020

-

5 reasons to host your Christmas party on a cruise boat - November 6, 2020

-

What to do when you’re charged with a crime - November 6, 2020

-

Should you get one or multiple dogs? Here’s all you need to know - November 3, 2020

-

A Guide: How to Build Your Very Own Magic Mirror - February 14, 2019

-

Our Top Inspirational Baseball Stars - November 24, 2018

-

Five Tech Tools That Will Help You Turn Your Blog into a Business - November 24, 2018

-

How to Indulge on Vacation without Expanding Your Waist - November 9, 2018

-

5 Strategies for Businesses to Appeal to Today’s Increasingly Mobile-Crazed Customers - November 9, 2018

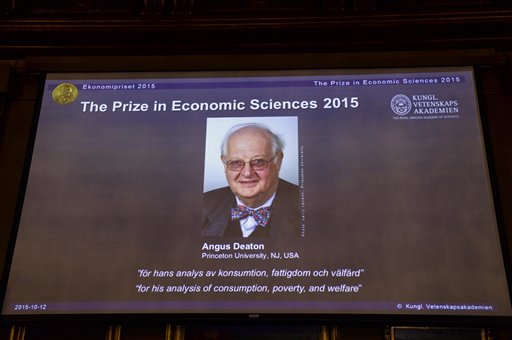

Angus Deaton Wins Nobel Economics Prize

Deaton’s contributions since the early 1980s have been widely recognised as shaping micro-, macro- and developmental economics, and for helping countries device effective welfare schemes to reduce poverty.

Advertisement

This year’s Sverges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences has been awarded to Angus Deaton, an economist who more than any other has helped us understand just why-and what-different people are consuming, mostly by simply asking them. Deaton, who also maintains a longstanding interest in the analysis of household surveys, noted that his focus on individuals and their decisions is important both from an academic and ethical standpoint, according to a report on the university website. Deaton’s refined understanding of how different consumers form their demand for goods and services based on their current needs, incomes and expectations of the future improved the theory of demand, dropping excessively restrictive and unrealistic conditions about consumer behaviour while retaining rationality as a valid attribute.

Deaton, a British and American citizen, is best known among economists for his insight that learning about the specific economic circumstances and choices of individuals, rather than relying on typical measures of larger groups, could produce a better perspective on the workings of the economy. Deaton co-wrote a paper in 1986 with applied macroeconomist John Muellbauer titled “On Measuring Child Costs: With Applications to Poor Countries”, which compared welfare levels between households of difference sizes and analyzed the measurement of child costs using household surveys.

The microeconomist, who was previously at Cambridge and Bristol universities said he was “surprised and delighted” by the award. On the process, Angus Deaton is very committed to the idea that public policy should be an outcome of democratic practice, as opposed, say, to professional expertise or randomised controlled trials.

Over the years, Deaton’s research has spanned a broad field.

He admitted that he always thought he would be unlikely to win the Nobel Prize, although his name has been on that list.

The economics prize is the newest of the Nobels, established in 1968, in Alfred Nobel’s memory, to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the Sweden’s central bank, the world’s first. However, Deaton is also an optimist-about his own field of study and the evolution of mankind generally.

“Angus Deaton is a brilliant economist whose pioneering research attacks big questions with rigor, imagination and daring”, said Princeton President Christopher L. Eisgruber. “Not having money can give you a perspective on the world that you don’t get other ways”, he said. His research was able to identify that varied individual reactions to income shocks-as a few incomes increase and others go down-tend to wash out in the aggregate, building a clearer picture of unequal consumption in the economy.

Advertisement

The youngest prize victor is Kenneth J. Arrow, who was awarded it in 1972, when he was 52 years old. The Nobel Prize committee made the announcement Monday saying that Prof. In this instance, though, I had called the wrong man. Instead of a pithy quote, I received a lengthy lecture on the difficulty of estimating the so-called wealth effect, the perils of drawing conclusions about individuals from aggregate statistics, the lopsided nature of wealth distribution in the United States, and much else besides. It’s their lives that are being led.