-

Tips for becoming a good boxer - November 6, 2020

-

7 expert tips for making your hens night a memorable one - November 6, 2020

-

5 reasons to host your Christmas party on a cruise boat - November 6, 2020

-

What to do when you’re charged with a crime - November 6, 2020

-

Should you get one or multiple dogs? Here’s all you need to know - November 3, 2020

-

A Guide: How to Build Your Very Own Magic Mirror - February 14, 2019

-

Our Top Inspirational Baseball Stars - November 24, 2018

-

Five Tech Tools That Will Help You Turn Your Blog into a Business - November 24, 2018

-

How to Indulge on Vacation without Expanding Your Waist - November 9, 2018

-

5 Strategies for Businesses to Appeal to Today’s Increasingly Mobile-Crazed Customers - November 9, 2018

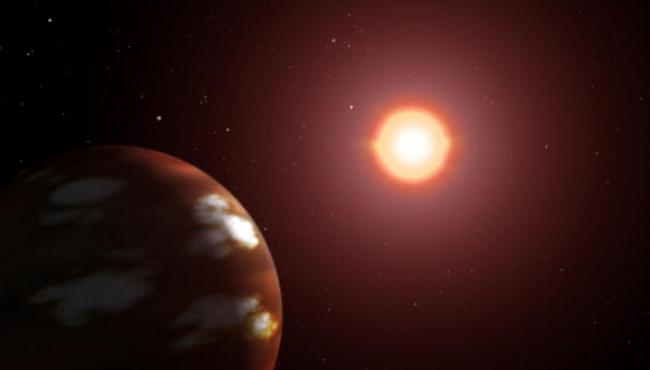

Astronomers witnessed the birth of two planets for the first time ever

For the first time, a team of astronomers and astrophysics have witnessed the planet formation of two or three small planets orbiting around sun-like star at a distance of about 430 light-years away from Earth. Such circumstellar disks commonly surround newborn stars, providing the raw materials from which planets form.

Advertisement

The observation was combined in the paper with data from Steph Sallum, the co-lead author and a graduate student at the University of Arizona, who independently observed the same star with a complementary technique.

Together, the two observations allowed the scientists to “unambiguously detect one planet”, Sallum says, which is now named LkCa-15b. “There have always been alternative explanations, but in this case we’ve taken a direct picture, and it’s hard to dispute that.” .

We’ve found almost 2000 exoplanets, but so far planetary formation has only been seen indirectly by studying gaps in large discs of dust and gas around stars.

By learning more about the young star system, scientists might be able to answer a few long-unanswered questions about how planets form, including the origins of Earth.

“It’s like a big doughnut”, said Follette.

For the first time astronomers directly observed a planet growing in its very early stages of life, and that’s quite a rare find: Of the almost 1,900 planets discovered outside of our solar system the infant planet, known as LkCa 15 b, is the only one known to be forming as you read this. They’re especially bright in hydrogen-alpha emissions, a particular shade of red that is very often useful in astronomy because it’s strongly emitted where hydrogen gas is ionized. In studying the growth of new exoplanet as it continues to collect matter, the research team is hoping to get a much better understanding of how our own planetary system – the solar system – formed and became what it is today. Dust accumulates and begins drawing in pebbles, then larger rocks, boulders, and ultimately the mash-up of debris coalesces to form a rocky core. It was discovered in 2011 by astronomers Adam Kraus and Michael Ireland using the Keck II telescope. Using MagAO’s unique ability to work in visible wavelengths, they captured the planet’s “hydrogen alpha” spectral fingerprint, the specific wavelength of light that LkCa 15 and its planets emit as they grow. But the scientists couldn’t see everything – and they think there may be more planets in the gap of the protoplanetary disk.

The Nature journal has published the exceptional study of the early formation of two planets.

Advertisement

Co-author Peter Tuthill from the University of Sydney said the images provided unambiguous evidence. The protoplanet is very close to its parent star, Follette said, and if it were much closer or fainter, LkCa 15 would have washed out its light completely.