-

Tips for becoming a good boxer - November 6, 2020

-

7 expert tips for making your hens night a memorable one - November 6, 2020

-

5 reasons to host your Christmas party on a cruise boat - November 6, 2020

-

What to do when you’re charged with a crime - November 6, 2020

-

Should you get one or multiple dogs? Here’s all you need to know - November 3, 2020

-

A Guide: How to Build Your Very Own Magic Mirror - February 14, 2019

-

Our Top Inspirational Baseball Stars - November 24, 2018

-

Five Tech Tools That Will Help You Turn Your Blog into a Business - November 24, 2018

-

How to Indulge on Vacation without Expanding Your Waist - November 9, 2018

-

5 Strategies for Businesses to Appeal to Today’s Increasingly Mobile-Crazed Customers - November 9, 2018

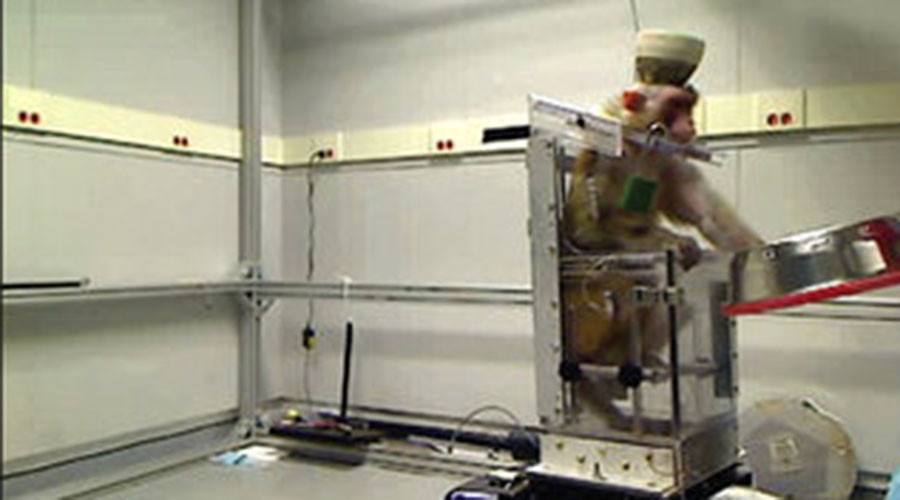

BMI Allowing Monkeys to Control Wheelchairs by Thought

Duke neuroscientist Miguel Nicolelis and his team first began experimenting back in 2012, when they implanted hundreds of microfibers as thin as a human hair in the brains of two rhesus macaque monkeys. The animals very quickly adapted to the technology.

Advertisement

Scientists implanted electrodes that enabled wireless recordings from a group of neurons that are associated with signals before and during movements. They rooted them in the sites responsible for limb movement and planning. The wireless BMI translated cortical activity in order to direct the speed and direction of the robotic wheelchair.

(A) The mobile robotic wheelchair, which seats a monkey, was moved from one of the three starting locations (dashed circles) to a grape dispenser.

At first, the monkeys were driven around in powered wheelchairs with their brains’ impulses recorded by an intracranial scanner, which later allowed for creating a steering algorithm. Researchers noted that the monkeys became more skilled at manipulating the device the more attempts they had to move it to the fruits. Study researchers said that these experiments will have significant implications in the real world.

The research is significant in that it could eventually be used to help people who are paralyzed get around, either with a high-tech wheelchair or more advanced robotic devices.

The researchers said that they want to build implantable suites of electrodes capable of recording the activity of several thousand. “I think we’re ready for it”. With this, scientists have been developing brain-machine interfaces (BMIs) to enhance such assistive devices and enable brain control to lead the navigation.

The newly developed interface can convert the lab animals’ thoughts into electric pulses that are further converted into movement by the computer embedded in the wheelchairs. “This wireless system could have particularly exciting implications for disabled people who have lost most muscle control and mobility due to quadriplegia or ALS, the researchers said”.

Nicolelis believes that the monkeys’ brain structures changed in response to training, which made them better and better at controlling the device over time.

Professor Miguel Nicolelis of Duke University in North Carolina, leading the project, told The Guardian: “The conclusion of this study is that you would be able to (put) this patient in a motorised electronic wheelchair and this patient would be able to learn to navigate this wheelchair freely, continuously, using an intra-cortical implant”.

In a statement provided to LATimes News, the monkeys were neither immobilized nor even strapped into their wheelchairs. Over time, the monkeys gained better control on the chair’s movements and were able to navigate to the grapes faster.

Advertisement

“That wheelchair was being assimilated by the brain as an extension of the monkey’s own body”, Nicolelis said.