-

Tips for becoming a good boxer - November 6, 2020

-

7 expert tips for making your hens night a memorable one - November 6, 2020

-

5 reasons to host your Christmas party on a cruise boat - November 6, 2020

-

What to do when you’re charged with a crime - November 6, 2020

-

Should you get one or multiple dogs? Here’s all you need to know - November 3, 2020

-

A Guide: How to Build Your Very Own Magic Mirror - February 14, 2019

-

Our Top Inspirational Baseball Stars - November 24, 2018

-

Five Tech Tools That Will Help You Turn Your Blog into a Business - November 24, 2018

-

How to Indulge on Vacation without Expanding Your Waist - November 9, 2018

-

5 Strategies for Businesses to Appeal to Today’s Increasingly Mobile-Crazed Customers - November 9, 2018

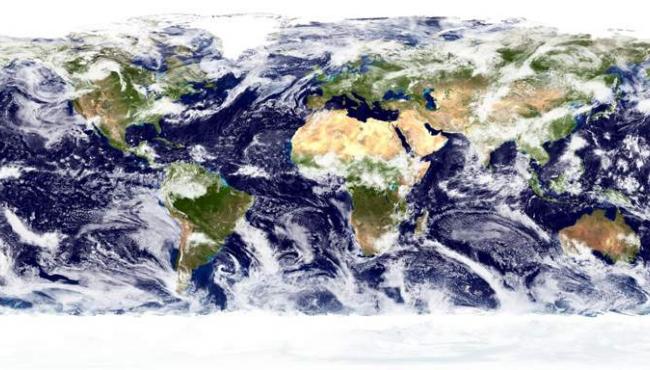

Climate change may be shifting clouds toward the poles

“What this paper brings to the table is the first credible demonstration that the cloud changes we expect from climate models and theory are now happening”, lead author Joel Norris, a climate researcher at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, said in a statement.

Advertisement

The biggest unknown in climate science just got a bit more known, and the results aren’t good.

Clouds play contradictory roles in the climate. So, the clouds are now reflecting less radiation from the planet than they would have reflected if they were closer to the tropics. This complex relationship makes it hard for scientists to understand the effects of clouds on climate and vice versa.

Scientists have been working on untangling that knot for decades. This is because researchers have to cobble together data on cloud patterns from existing satellite observations.

These cloud changes are, of course, hardly without effect – the growth of so-called dry zones or drylands, as the planet warms, has been long predicted and indeed, observed by climate scientists.

Clouds haven’t disappeared, however, one only needs to look up to see that we’re still okay for now. Satellite coverage goes back only to the late 1970s, with technologies designed for weather monitoring.

Norris and his team corrected these alterations in cloud data records from 1983 to 2009. Their research shows that since the 1980s, the world is cloudier toward the poles and less cloudy in the midlatitudes.

Clouds regulate the Earth’s temperature by sending into space a portion of solar radiation before they touch the ground.

The biggest cloud effect on the reflection of solar radiation occurs in ocean regions where having fewer clouds means more heat is absorbed by the relatively dark surface of the seas.

Why has a warmer world allowed clouds to reach higher into the atmosphere, thickening the cloud blanket and further encouraging warming?

So how did those patterns stack up against the climate models? Political priorities change, budgets drop, technology evolves, and climate scientists are left having to extract consistent, long-term data from measurements taken without the long term in mind.

Clouds aren’t as simple as their fluffy nature might suggest.

Namely, the observations showed that the main area of storm tracks in the middle latitudes of both hemispheres shifted poleward, expanding the area of dryness in the subtropics, and that the height of the highest cloud tops had increased. But the error bars on this assessment were huge, wide enough to include the possibilities that clouds could potentially offset about half of global warming, or actually cause warming themselves. The new work meshes well with the earlier findings, Eastman says.

“What was lacking was observational confirmation due to artefacts present in the satellite cloud record that overwhelmed any real signal”.

Next up for the study’s authors is to untangle further how natural events, such as volcanoes, and greenhouse-led warming contribute to the cloud changes.

“It gives us some confidence, the fact that these basic processes are lining up as expected, that we can build on those in the future and attempt to get a better quantitative understanding of how the clouds amplify greenhouse gas warming”, Dr. Donner tells the Monitor in a phone interview Monday.

Advertisement

Bjorn Stevens, a meteorologist of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology in Hamburg, Germany, stated that the study also reveals how inadequate are the cloud observing systems when it comes to fundamental climate questions.