-

Tips for becoming a good boxer - November 6, 2020

-

7 expert tips for making your hens night a memorable one - November 6, 2020

-

5 reasons to host your Christmas party on a cruise boat - November 6, 2020

-

What to do when you’re charged with a crime - November 6, 2020

-

Should you get one or multiple dogs? Here’s all you need to know - November 3, 2020

-

A Guide: How to Build Your Very Own Magic Mirror - February 14, 2019

-

Our Top Inspirational Baseball Stars - November 24, 2018

-

Five Tech Tools That Will Help You Turn Your Blog into a Business - November 24, 2018

-

How to Indulge on Vacation without Expanding Your Waist - November 9, 2018

-

5 Strategies for Businesses to Appeal to Today’s Increasingly Mobile-Crazed Customers - November 9, 2018

Cosmic curveball: Is the universe expanding even faster?

The most recent calculation of the universe’s rate of expansion, called the Hubble constant, is believed to be the most accurate ever – with a margin of error, or rate of uncertainty, of just 2.4 percent.

Advertisement

Galaxies are accelerating away from each other 5% to 9% faster than had previously been thought, according to scientists. The number they came up with was 5 to 9 per cent faster than other scientifically accepted measurements that calculate the expansion rate based on cosmic background radiation from 380,000 years after the so-called Big Bang.

“Maybe the universe is tricking us, or our understanding of the universe isn’t complete”, he added. That means in 9.8 billion years the distance between cosmic objects will double. And it could be that Einstein’s General Relativity just isn’t quite right when we look at the whole universe.

An global team of researchers led by Professor Adam Riess of the Space Telescope Science Institute and The Johns Hopkins University have made the most accurate measurements so far of the universe’s rate of expansion following the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago. Riess is a former UC Berkeley post-doctoral fellow who worked with Filippenko.

The results will appear in an upcoming issue of The Astrophysical Journal. This would have sped up the expansion of the early universe and would explain the discrepancies in current theory.

The new Hubble constant is now 73.2 kilometres per second per megaparsec.

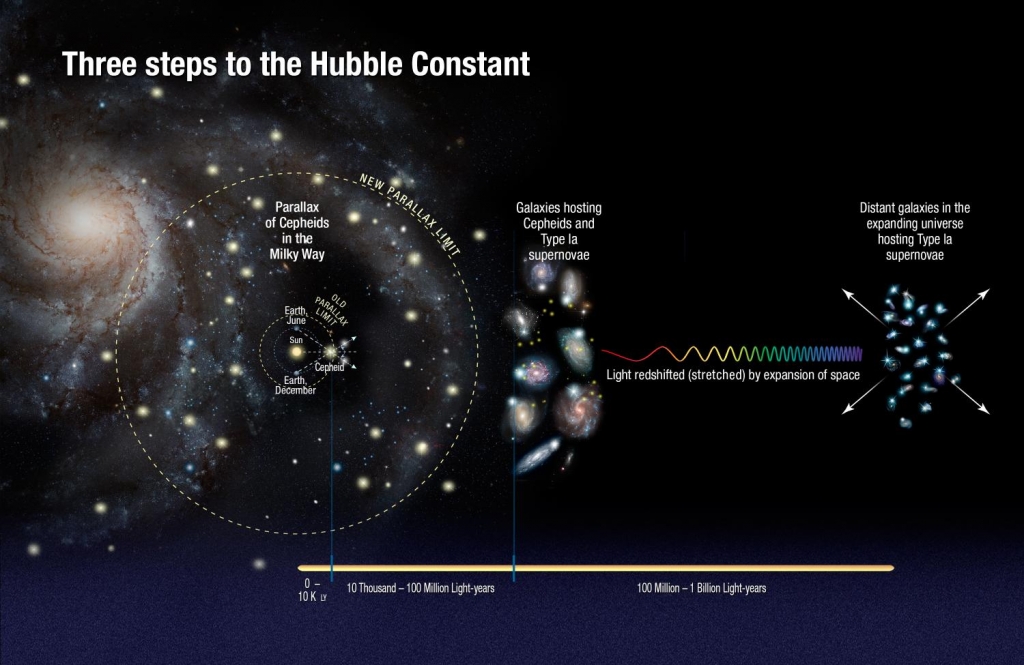

Astronomers use Cepheid variables, a type of star whose luminosity and pulsation period indicates distance, within the Milky Way.

Previous direct measurements of galaxies pegged the current expansion rate, or Hubble constant, between 70 and 75 km/sec/Mpc, give or take about 5-10 percent – a result that is not definitely in conflict with the Planck predictions.

Pulsating Cepheid variable stars and Type Ia supernovae were used to calculate how fast the Universe expands. Cepheid stars pulsate at rates that correspond to their true brightness, which can be compared with their apparent brightness as seen from Earth to accurately determine their distance.

“We compare those distance measurements with how the light from the supernovae is stretched to longer wavelengths by the expansion of space”, the astronomers said. “The paper focuses on the 19 galaxies and getting their distances really, really well, with small uncertainties, and thoroughly understanding those uncertainties”.

This refined determination of the Hubble constant was made possible by making precise measurements of the distances to both nearby and faraway galaxies using Hubble [2]. Once astronomers calibrate the Cepheids’ true brightness, they can use them as cosmic yardsticks to measure distances to galaxies much farther away than they can with the parallax technique.

“There’s potentially something very exciting, very interesting that the data is trying to tell us about the universe, ” Filippenko said. It’s also possible that “dark radiation” – an unknown, superspeedy subatomic particle or particles that existed shortly after the Big Bang – could be playing a role that hasn’t been taken into account, the researchers said.

Dark matter and the dark energy it carries may explain the acceleration of the universe’s expansion.

The team used the Hubble’s sharp-eyed Wide Field Camera 3, and its observations were managed by the Supernova H0 for the Equation of State (SH0ES) team.

As it was already mentioned, there is no clear reason as why the predictions made with the beginning-of-times data do not match with the corrected values for the Hubble constant.

Advertisement

A goal of 1 percent has been set by SH0ES and the possible devices that would allow such accuracy could be the European Space Agency’s Gaia satellite, and future telescopes such as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) that is set to replace the Hubble.