-

Tips for becoming a good boxer - November 6, 2020

-

7 expert tips for making your hens night a memorable one - November 6, 2020

-

5 reasons to host your Christmas party on a cruise boat - November 6, 2020

-

What to do when you’re charged with a crime - November 6, 2020

-

Should you get one or multiple dogs? Here’s all you need to know - November 3, 2020

-

A Guide: How to Build Your Very Own Magic Mirror - February 14, 2019

-

Our Top Inspirational Baseball Stars - November 24, 2018

-

Five Tech Tools That Will Help You Turn Your Blog into a Business - November 24, 2018

-

How to Indulge on Vacation without Expanding Your Waist - November 9, 2018

-

5 Strategies for Businesses to Appeal to Today’s Increasingly Mobile-Crazed Customers - November 9, 2018

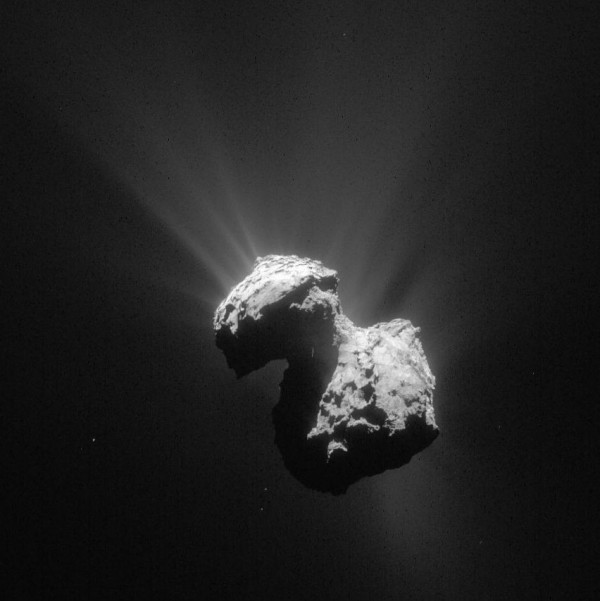

Cycle of ice turning to gas may feed comets’ tails

The team behind the discovery suspects that the ice is replenished from below, through fissures that grow during the day as the sun’s intense rays scorch the surface. When the sun rises, the molecules in the newest ice layer sublimate, and the whole outgassing cycle starts over. The observations focused a square-kilometer area on the “neck” connecting the two lobes of the comet.

Advertisement

“We saw the tell-tale signature of water ice in the spectra of the study region but only when certain portions were cast in shadow”, De Sanctis said. Rosetta’s Philae lander is contributed by a consortium led by DLR, MPS, CNES and ASI.ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft has provided evidence for a daily water-ice cycle on and near the surface of comets. During the comet’s local day, water ice on and a few centimetres below the surface sublimates and escapes; during the comet’s local night, the surface rapidly cools while the underlying layers are still warm, so subsurface water ice continues sublimating and finding its way to the surface, where it freezes again.

The ice was spotted in data gathered last August using Rosetta’s VIRTIS instrument – a spectrometer created to map the comet’s chemical composition. “When the Sun was shining on these regions, the ice was gone.”This suggests that water ice on and a few centimeters below the surface turns to gas when lit up, then flows away, she explained.Then, as darkness returns, the surface quickly gets cold again”.

Fabrizio Capaccioni, VIRTIS principal investigator at INAF-IAPS in Rome, Italy, says that this mechanism could be at play on all comets and Rosetta’s extensive monitoring at 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko has provided observational proof. As the comet rotates, parts of it pass into and out of the sunlight, leading to different processes.

From these data, it is possible to estimate the relative abundance of water ice with respect to other material.

But whereas on Earth this warming and cooling would see rain falling back to the planet’s surface, Comet 67P is hurtling through space at around 135,000 km/h (84,000 mph) and the water vapor is being whipped away from its surface.

The water-ice cycle of Rosetta’s comet.

“How and where exactly the sources of cometary activity arise has been a largely unsolved mystery in comet research”, said co-author Dr Gabriele Arnold of the German Aerospace Center.

The finding helps resolve a puzzle about why a comet’s surface can be relatively free of ice, such as what has been observed on 67P and other comets, even though the bodies are outgassing water.

Advertisement

“Rosetta is capable of tracking changes on the comet over short as well as longer time scales, and we are looking forward to combining all of this information to understand the evolution of this and other comets”.