-

Tips for becoming a good boxer - November 6, 2020

-

7 expert tips for making your hens night a memorable one - November 6, 2020

-

5 reasons to host your Christmas party on a cruise boat - November 6, 2020

-

What to do when you’re charged with a crime - November 6, 2020

-

Should you get one or multiple dogs? Here’s all you need to know - November 3, 2020

-

A Guide: How to Build Your Very Own Magic Mirror - February 14, 2019

-

Our Top Inspirational Baseball Stars - November 24, 2018

-

Five Tech Tools That Will Help You Turn Your Blog into a Business - November 24, 2018

-

How to Indulge on Vacation without Expanding Your Waist - November 9, 2018

-

5 Strategies for Businesses to Appeal to Today’s Increasingly Mobile-Crazed Customers - November 9, 2018

Just a burp: Intriguing hints of physics particle evaporate

New particles discovery, which may prompt a paradigm shift in physics, is probably still years away.

Advertisement

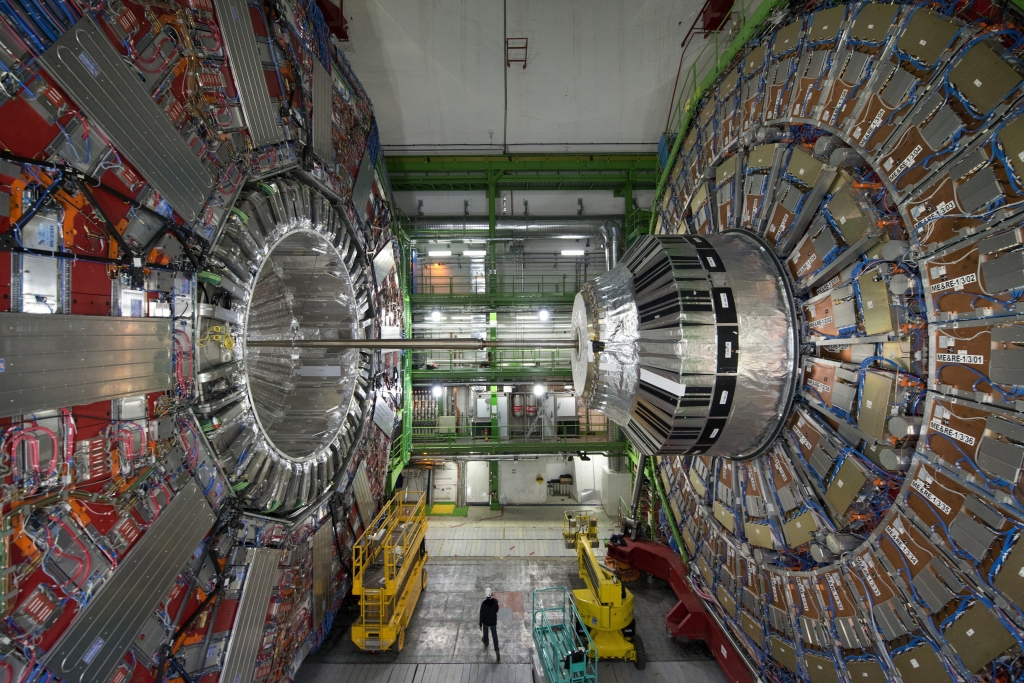

Disappointed physicists from the Large Hadron Collider report that what initially could have been an intriguing new particle has turned out just to a statistical burp.

However, hints of the new particle disappeared Friday, August 5. The LHC, which includes a tunnel-shaped ring of 27 km, has already in 2012 confirmed the existence of the Higgs boson, considered the cornerstone of the fundamental structure of matter.

The search for new particles in data from the LHC starts with a calculation of the sorts of things we should expect to see at a given energy. Physicists from CERN presented more than 50 new results, but none of them are breakthrough findings that would change current theory.

This “diphoton bump” was not a prediction of the Standard Model of physics-a rigorously tested and profoundly successful theory forged in the 1970s that incorporates all known fundamental particles and forces.

Speaking to journalists in Chicago at the International Conference on High Energy Physics (ICHEP), Prof Charlton said it was a remarkable coincidence – but purely a coincidence – that two separate LHC detectors, Atlas and CMS, picked up matching “bumps”.

There were suggestions the spike might be evidence of heavier particles like gravitons, which are the theoretical particles responsible for the effects of gravity. But, he added, noting that the experimenters had always cautioned that the bump was most likely a fluke, “We have always been very cool about it”. Now, after analyzing almost five times the amount of data that they had previous year, ATLAS and CMS physicists have watched the bump diminish to statistical insignificance. Simply put, the diphoton bump was a false alarm.

If proven, the discovery might have been considered an elementary particle that is not part of the Standard Model and might have cracked open a line between the known and the unknown. The multibillion-dollar project has years of operations left during which it will produce far more data for physicists to parse for elusive new particles.

Advertisement

“Basically we see nothing”, said Tiziano Camporesi, a chief scientific spokesman at the European Centre for Nuclear Research (Cern).