-

Tips for becoming a good boxer - November 6, 2020

-

7 expert tips for making your hens night a memorable one - November 6, 2020

-

5 reasons to host your Christmas party on a cruise boat - November 6, 2020

-

What to do when you’re charged with a crime - November 6, 2020

-

Should you get one or multiple dogs? Here’s all you need to know - November 3, 2020

-

A Guide: How to Build Your Very Own Magic Mirror - February 14, 2019

-

Our Top Inspirational Baseball Stars - November 24, 2018

-

Five Tech Tools That Will Help You Turn Your Blog into a Business - November 24, 2018

-

How to Indulge on Vacation without Expanding Your Waist - November 9, 2018

-

5 Strategies for Businesses to Appeal to Today’s Increasingly Mobile-Crazed Customers - November 9, 2018

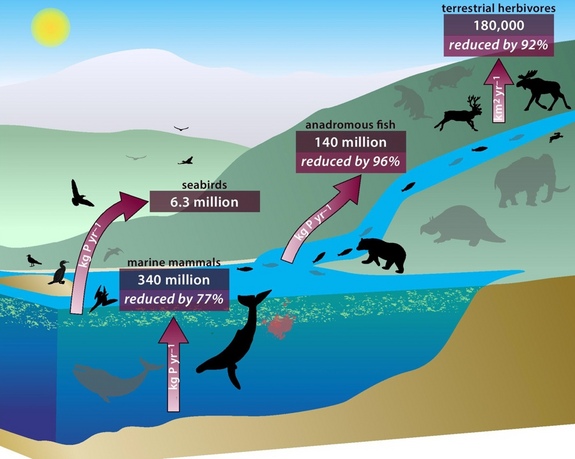

S–t doesn’t happen: Large mammals absence disrupts ecosystem fertilization

“We estimate that the capacity of animals to move nutrients away from concentration patches has decreased to about 8 percent of the pre-extinction value on land and about 5 percent of historic values in oceans”. In particular, their poop.

Advertisement

This diagram shows how animals carry nutrients through their poop, urine, and decomposing bodies.

According to Joe Roman, biologist from University of Vermont, approximately 150 species of large mammals became extinct about 10,000 years ago.

Of 48 species of the very largest plant-eating land mammals alive during the Ice Age, including 16 species of elephants and their relatives, nine rhinoceros species and eight giant sloth species, only nine remain, none in the Americas, Doughty said.

It’s probably no surprise to learn that humans have had a hand in disrupting this ecosystem balance.

For instance, researchers estimate that before the era of commercial hunting, whales and other marine mammals moved around 750 million pounds (340 million kilograms) of phosphorus from the depths to the surface each year.

A new study reveals that in the past large land animals, whales, seabirds and fish played a vital role in recycling nutrients from the ocean depths, spreading them far and wide across the globe and taking them deep inland.

Restoring the populations of large mammals and sea creatures through conservation could help fight the damage being caused by global warming, by absorbing more carbon dioxide in the oceans and replenishing landscapes across the planet, said the findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a peer-reviewed U.S. journal.

Animal manure is considered as organic fertilizers.

In the past animals were not believed to be vital for nutrient transfer, but this new research demonstrates the animals are crucial for the “distribution pump” of fecal matter that fertilizes naturally barren areas. There, nutrients are consumed by phytoplankton on the ocean’s surface, leading to more phytoplankton for predators like whales to eat, which eventually leads to more whales. This view assumed that the role of animals was minor, and mostly that of a passive consumer of nutrients.

“…recovery is possible and important”, said Roman.

“I wanted to know whether the world of the past with all the endemic animals was more fertile than our current world”, lead study author Chris Doughty of Oxford University told The Post. “Restoring populations of animals could help to recycle phosphorus from the sea to land increasing global stocks of available phosphorus in the future”.

Dr Roman said: ‘The typical flow of nutrients is down mountains to the oceans.

‘We are looking at ways that nutrients can go in the other direction-and that’s largely through foraging animals. But since its peak, the capacity for whales and other marine mammals to transport it from the deep sea to water surface has dropped about 75 percent.

‘It might be a challenge policy-wise, but it’s certainly within our power to bring back herds of bison to North America.

Advertisement

David B Fleetham/Getty Images/Photolibrary RM Phosphorus is a nutrient essential for healthy plants and agriculture.