-

Tips for becoming a good boxer - November 6, 2020

-

7 expert tips for making your hens night a memorable one - November 6, 2020

-

5 reasons to host your Christmas party on a cruise boat - November 6, 2020

-

What to do when you’re charged with a crime - November 6, 2020

-

Should you get one or multiple dogs? Here’s all you need to know - November 3, 2020

-

A Guide: How to Build Your Very Own Magic Mirror - February 14, 2019

-

Our Top Inspirational Baseball Stars - November 24, 2018

-

Five Tech Tools That Will Help You Turn Your Blog into a Business - November 24, 2018

-

How to Indulge on Vacation without Expanding Your Waist - November 9, 2018

-

5 Strategies for Businesses to Appeal to Today’s Increasingly Mobile-Crazed Customers - November 9, 2018

Scientists call for a ban on genetically modifying human embryos

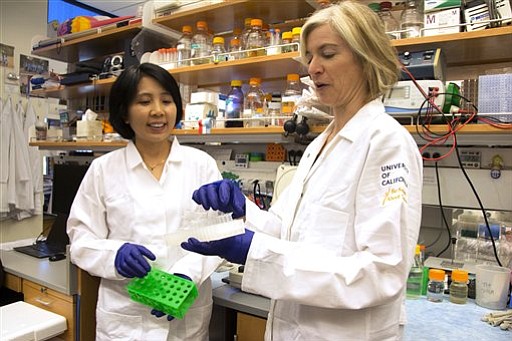

In this photo provided by UC Berkeley Public Affairs, taken June…

Advertisement

Nobel laureate David Baltimore of CalTech speaks to reporters at… But the research sparked criticism and renewed concern for the ethical use of such powerful genetic tools. CRISPR-Cas9 is quick and precise, and has already been adopted by thousands of labs around the world.

“Before we make permanent changes to the human gene pool, we should exercise considerable caution”, the Broad Institute’s Dr. Eric Lander said.

“Genetic modification has been exploding in the scientific scene”, she said. John Holdren of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy said that “is a line that should not be crossed at this time”. We are not yet at that point. But it’s critical, particularly as scientists and regulators start making decisions. “But more studies are needed and ethical debates about when we should use gene editing will no doubt continue”.

Altering genes in sperm, eggs or embryos can spread those changes to future generations, so-called germline engineering that might one day stop parents from passing inherited diseases to their children. Better potatoes. Genetically modified human embryos. Although the embryos were “non-viable”, it was an unprecedented development. “But this needs to be discussed in the context of this meeting and future meetings so that we can really determine the path forward for gene editing”. “CRISPR is made up of scissors in the form of an enzyme that cuts DNA strands and an RNA guide that knows where to make the cut, so the traits expressed by the gene are changed”. Doudna and her colleague Emmanuelle Charpentier altered it to target and cut very specific regions of DNA in humans and other animals, so that it is now possible to cut one gene only in a human genome of 20,000 genes. It was used to replace the problem gene and turn off the condition by sending a combination of protein and RNA to bind and overhaul a gene.

Germline editing, during which reproductive cells are modified, stands in contrast to other gene-editing techniques that can be used to alter non-reproductive cells in order to treat impaired human tissue, the group said.

Changes in adults would affect only one person, though.

Among them are Dr Michael Antoniou, Head of the Gene Expression and Therapy Group at Kings College London and Professor Donna Dickinson, emeritus professor of medical ethics at the University of London.

Some prominent scientists in the United States have called for a moratorium or ban on the genetic modification of children and future generations, after major developments in genetic engineering and synthetic biology, which, they say, could potentially have irreversible and monumental effects on humanity. Some countries, especially in Europe, ban germline research.

Not everyone agrees that new guidelines are necessary. Some scientists suggest imposing a ban on research will only result in practice moving underground to “black markets”. Or it could allow researchers to patch an extra gene into a human genome that could recover crippled cells.

Advertisement

Doudna is looking forward to the discussion this week and hopes for a consensus, though that outcome is far from certain. Bioethicist Insoo Hyun of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, said that genetically engineered immune cell treatments (such as those helping with muscle wasting in AIDS or cancer patients) could get in the hands of athletes for illicit use. “I like everyone else in the world am concerned with the implications of this new technique”, Kevles said.