-

Tips for becoming a good boxer - November 6, 2020

-

7 expert tips for making your hens night a memorable one - November 6, 2020

-

5 reasons to host your Christmas party on a cruise boat - November 6, 2020

-

What to do when you’re charged with a crime - November 6, 2020

-

Should you get one or multiple dogs? Here’s all you need to know - November 3, 2020

-

A Guide: How to Build Your Very Own Magic Mirror - February 14, 2019

-

Our Top Inspirational Baseball Stars - November 24, 2018

-

Five Tech Tools That Will Help You Turn Your Blog into a Business - November 24, 2018

-

How to Indulge on Vacation without Expanding Your Waist - November 9, 2018

-

5 Strategies for Businesses to Appeal to Today’s Increasingly Mobile-Crazed Customers - November 9, 2018

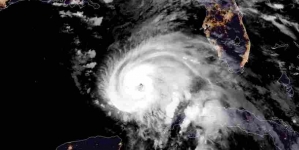

Why Beirut bombings went unnoticed?

Well, you don’t have to look too hard to find that many victims in Paris were also of Arabic descent.

Advertisement

Then there’s the social-media component to consider. And also on Friday, a bombing in Baghdad, Iraq claimed 26 lives and injured “dozens” more, according to Al Jazeera. Many of us have been criticized for overlaying our Facebook profile with the French flag, but this isn’t the time for political discussion.

Facebook has since launched its security check feature and hundreds are being “marked safe” to the relief of family and friends around the world.

Sympathy-shaming was all the rage on social media over the weekend in the wake of the Paris attacks.

The attack that targeted the Shia-majority district of Burj al-Barajneh was the first major suicide bombing ever reported in the country, with the number of casualties expected to increase as search and rescue operations continue. But from a human-behavior standpoint, more interesting is the model of the “proper” response to death and destruction posited by Kohn, Nunn, and others. During our years here we will be exposed to a broader range of experience and thought than at likely any other time in our lives. Or perhaps victims of violence in the Middle East are dehumanized by stereotypes.

Its vice-president of growth, Alex Schultz, who was referred to by Zuckerberg in his comment, explained in another, longer post that Safety Check was not activated during the Beirut attacks because it is not that useful “during an ongoing crisis, like war or epidemic” as it is impossible to know when someone is truly “safe”.

The outpouring of support for Paris has been mostly inspiring, but one class of reaction has been especially odd: the scolds who chide our hypocrisy for caring so much about predominantly white, European victims while reacting less emotionally to the plight of the victims of terrorist attacks elsewhere.

Yet two attacks carried out by the Islamic State just one day apart have revealed a stark difference in the way violence in these two cities is perceived.

The lack of coverage is not accidental. These attacks weren’t necessarily portrayed as stories that could stand on their own, they seemed to only be relevant in the context of what happened in France’s capital. Even many Arabs are being chided for expressing more empathy with the French than with the Lebanese. Almost 50 people were killed in a bombing for which Isis claimed responsibility. Among the few headlines Beirut has received, most were phrased to incite sectarian blame by referring to the bombed area a “Hezbollah stronghold” in order to politicize the death of civilians.

Bubbling underneath all of this unity, however, has been a persistent question: why did the world stop for Paris and not, say, Beirut, where ISIS bombs killed 43 civilians just a day before the horrors in France? But let us take this moment to quietly grieve these awful attacks on humanity. President Obama pushes the trite and racist narrative that we are somehow uncivilized and thus such attacks are commonplace and insignificant.

Being half Lebanese and half Syrian, these recent events are personal. To be truthful, I did not imagine that my heart would break for a country I barely remember, and my tears at hearing the anthem at Monday’s vigil took me by surprise. Although I have never been to Syria, and haven’t been to Lebanon since I was a child, I know it could have been my family and me in Beirut. It could have been us as refugees, fleeing Syria from the very same terror inflicted on Paris. Imagine losing a loved one in this attack only to be told you don’t care enough about the loss of Lebanese citizens. Mourn for those killed in Iraq, Yemen and Palestine by Western-backed regimes. There was a collective silence from the west and the western media.

Advertisement

“When my people died, they did not send the world into mourning”. On the Margin runs alternate Wednesdays this semester.